The 9-11 Commission stated six primary reasons for restructuring the Intelligence Community. First on the list was that information was not organized. The Commission argued that the importance of “…integrated, all-source analysis cannot be overstated. Without it, it is not possible to ‘connect the dots.’” But what were the dots? Were they data, information, or intelligence? Those dots were pieces of data with no overarching context for their collective meaning because agencies kept their type of data—and likely all their data—separated from other organizations. Because of this separation, the data never made the leap to become information.

The US government, small and large companies, and everyday people are swimming in data. We see images, news bites, and even longer stories that overwhelm us with information overload and seldom put things in any real order.

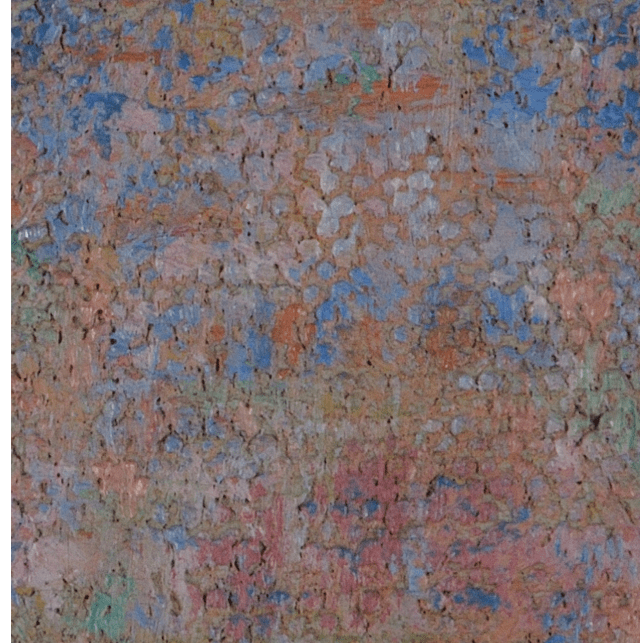

Imagine that your data is presented as a painting using the impressionist method called pointillism. The pointillist method of using small dots to create a larger whole represented a major shift in the approach to painting, as pointillists created various colors using single dots of the same four-color printing process used today, known as CMYK—cyan, magenta, yellow, and key (black), rather than the traditional method of mixing pigments on a palette. You might have seen something similar if you’ve ever looked closely at your television set and noticed that the colors are actually a complex arrangement of red, green, and blue cells.

Your data is much like the dots of a pointillist work. Individually they tell us little, but carefully expanding the canvas and adding more dots causes a figure to emerge.

Out of context, the dots don’t look like much.

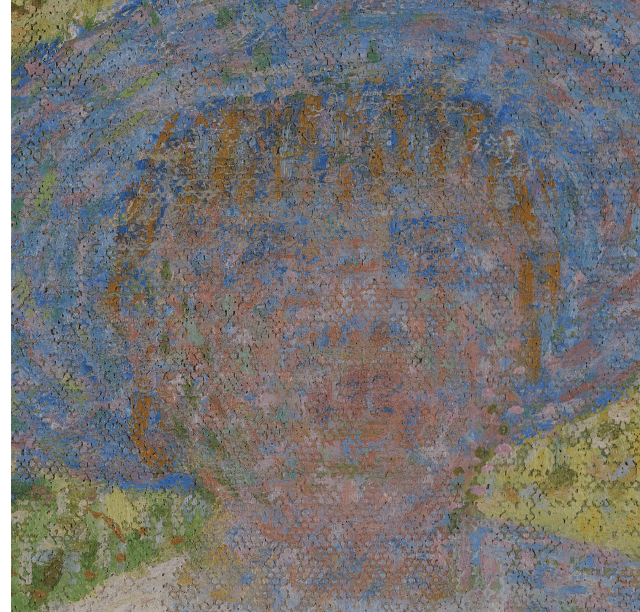

We see the dots create the face of a little girl. Once the dots have been collected, organized, and recognized, they become information. But they are not yet intelligence—that requires greater context. We don’t know who the girl is, where she is, or what she is doing.

As more dots are added we see that the girl is wearing a hat.

By continuing to zoom away from individual dots, it becomes clear that the girl is with a woman (likely her mother), walking along the Seine River River at La Grande Jatte, a park in Paris. The painting, of course, is by Georges Seurat. (Bonus points to anyone who gets the movie reference.)

Seurat was deliberate in the way he placed dots of different colors next to each other to create something meaningful. It wasn’t happenstance. Similarly, it is more effective to be deliberate with the way you organize and contextualize your data.

Lastly, despite the beauty and intelligence derived from the whole, remember that each dot remains. The entire work would not be possible without millions of dots performing in sync with one another.

Our data can become information, which in turn can become intelligence. Too often we want to see the final painting without taking the time to establish each piece of data in its respective space. Proper arrangement and context are key.

Sometimes the future appears obvious. Sometimes it is elusive. Without collecting data; recognizing patterns, forms, and reference; and providing context to make it information, the future is little more than a bunch of unconnected dots.

Geoff Openshaw contributed to this piece.

Related posts

Beyond Cultural Training: Turkey and the Case for Context

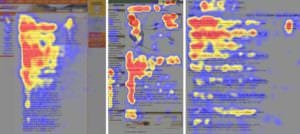

Reading or Skimming: Writing for How People Read Online

Choosing the Right Image for the Web